Factory farming and the price of meat

Posted on July 23, 2013

There is no doubt that factory farming in animal agriculture—with all the animal suffering that it entails—enables the meat industry to reduce the cost of producing meat. Not surprisingly, it is often assumed without a closer examination that factory farming has been essential to keeping down the price consumers pay for meat. Even when the mainstream media writes a piece critical of factory farming, this tacit assumption often guides the story.

Naturally, when criticized for the abuses of factory farming, the industry sometimes chooses this line of defense. It argues that rolling back factory farming and improving animal welfare will leave it no choice but to raise the price of meat. It claims that the rise in factory farming has been essential to keeping meat as cheap and affordable as it has been.

But, this industry claim is valid only if all three of the following conditions hold true:

- Condition 1: The cost savings from increased factory farming are actually passed on to the consumers of meat.

- Condition 2: The cost savings from improved efficiency in operations unrelated to factory farming (e.g., retail) are also passed on to the consumers of meat. (If this condition is not met, it is hard to argue that increased factory farming was essential since these other cost savings may have brought the retail price down to the same level without it.)

- Condition 3: Ways to reduce costs other than factory farming are not ignored, so that savings secured with increased factory farming do not just become an excuse to overlook unnecessary inefficiencies in other operations within the industry. (If this condition is not met, as in the case of Condition 2, it is hard to argue that increased factory farming was essential to keeping down the price of meat.)

As I will argue in this post, there is no evidence that the meat industry has met all these three conditions at least since 1980 even as both the intensity and the prevalence of factory farming sharply increased during this period. I begin in 1980 because most of the price data discussed in this post are available only for the period since 1980.

I will consider two of the largest components of the meat industry where factory farming is pervasive: the pork industry which sells the meat of pigs and the broiler industry which sells the meat of chickens.

On the price of pork

I will begin with a peek into the prices in the pork industry at three stages in the economic cycle of the product. One is the farm price, the price at which farmers sell the pigs to meatpackers like Smithfield and Tyson for slaughter and processing. The second is the wholesale price, the price at which meatpackers sell the pork to retailers like Walmart and Kroger. The third is the retail price, the price at which retailers sell the pork to the consumers.

In the following graph, using meat price spread data from the Economic Research Service at the USDA, I plot the farm price, the wholesale price and the retail price per pound of retail weight of pork between 1980 and 2012 (along with approximate trend-lines). I adjusted these prices for inflation using the Consumer Price Index tables provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics; any reference to a price in this post is always a reference to an inflation-adjusted price in June 2013 dollars or cents.

Even a cursory look at the graph above reveals that there have been two distinct long-term trends in the farm price since 1980: one from 1980 to 1999 and the other from 1999 to 2012. Between 1980 and 1999, the farm price of pork declined at a more or less constant rate. Then, between 1999 and 2012, interestingly, the farm price held more or less steady at the approximately same inflation-adjusted price. What happened here?

The price of pork: 1980-1999

The farm price and the wholesale price encapsulate within them a large part of the cost savings to the industry of factory farming, such as from intensive confinement of sows or indifferent assembly-line slaughter. The period from 1980 to 1999 saw a steady rise in factory farming; according to the USDA Census of Agriculture publications, between 1978 and 2002 the percentage of pigs sold by farms that sold more than a thousand pigs each year went from less than 35% to over 95%! This rise was the sharpest in the mid-1990s. Meanwhile, much consolidation in the industry led to only a few meatpackers (Smithfield, IBP, Swift, Excel, Farmland, and Hormel Foods) controlling more than 75% of the market.

- B. Walsh. Getting Real About the High Price of Cheap Food, Time Magazine, August 21, 2009.

- USDA, Economic Research Service. Meat Price Spreads. July 16, 2013. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index: All Urban Consumers. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- USDA. 1982-2007 Census of Agriculture. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- D. Barboza. The Great Pork Gap; Hog Prices Have Plummeted. Why Haven’t Store Prices?, The New York Times, January 7, 1999. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- T. Fredrickson. Hogs Lead Smithfield to Record Profits in ’99, Daily Press, June 11, 1999. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- Press release. Kroger Reports Record Earnings, The Kroger Company, 2000. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- David Kirby. Animal Factory: The Looming Threat of Industrial Pig, Dairy, and Poultry Farms to Humans and the Environment, 2011. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

As the figure shows, the period from 1980 to 1999 also saw a steady decline in the price farmers got paid for pigs they sold to processors. As the farm price continued to drop, only the factory farmers with thousands of pigs could stay in business, and many small traditional farms either got out of the business or converted to factory farming. There was much speculation about price-fixing; the US Agriculture Secretary even asked the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission to investigate. With only a few buyers to whom farmers could sell their pigs, it became what economists call an oligopsonistic market (similar to an oligopolistic market, except that instead of too few sellers, you had too few buyers making possible anti-competitive practices). During this time—due to illegal price-fixing or due to the relentless rise of factory farming or both—the farm price fell sharply and small farmers were run out of business while the meatpackers and retailers posted record profits for themselves. Some regions got hit harder than others—Animal Factory by David Kirby recounts the case of a farmer in Iowa who could only secure 8 cents per pound for his pigs near the end of 1998.

So, what happened to the retail price of pork during this time? Each drop in the farm price did result in a corresponding drop in the retail price. Now, is that all that one should expect out of the retail price? A quick note is worth injecting here—year-by-year fluctuations in the retail price will always follow and somewhat echo the fluctuations in the farm price, but this alone is not evidence that increased factory farming is increased savings for consumers of pork. For example, the farm price can fluctuate because of oversupply or undersupply, and these fluctuations may be mirrored in the retail price but they may not reflect the changing costs of production due to factory farming.

Ideally, to examine the impact of the savings secured from factory farming on the retail price, one has to examine the actual long-term trends against the long-term trends one expects from both the steady rise of factory farming and all other changes in the economy. For this, I will capture long-term trends with best-fit trend-lines through price data for pork and then compare against changes in the retail price of non-meat food products during the period between 1980 and 1999.

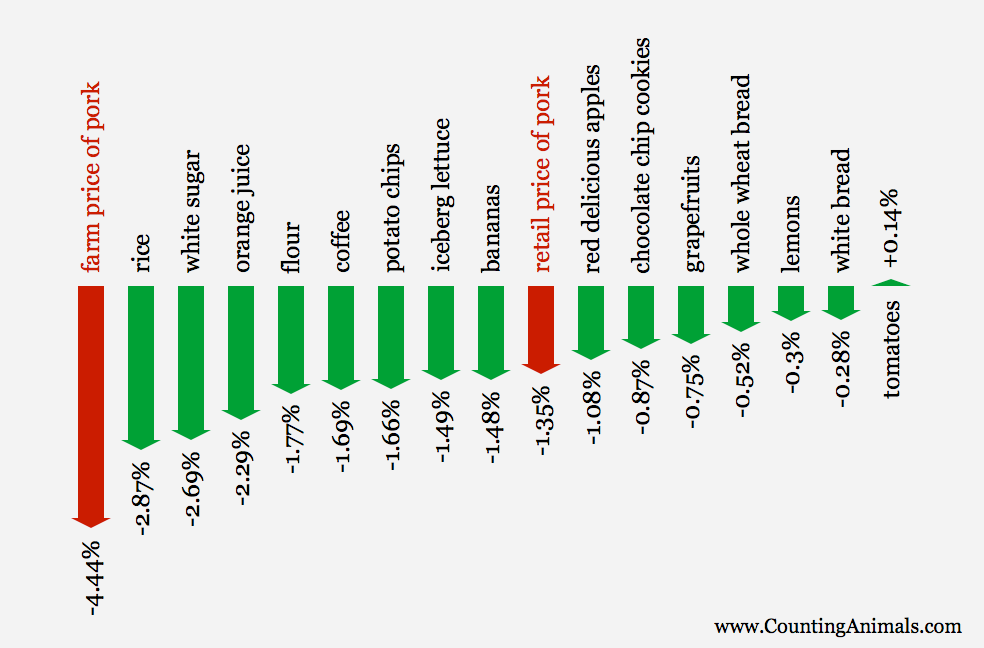

The Bureau of Labor Statistics compiles historical price data on a variety of food items and other consumer goods. I took every non-meat food item for which most of the monthly price data is available between 1980 and 1999 and used exponential regression to come up with an annual percentage change in the inflation-adjusted price of each item. Here is what I found.

So, the fall in the retail price of pork was hardly remarkable even though the fall in the farm price of pork, thanks to the radical approach of factory farming, was remarkable. In fact, the retail prices of many non-meat food items fell more than the retail price of pork.

Now, one may argue that there is something special about meat products which made it harder for prices to drop as much as they did for non-meat food items. So, let’s look at how prices of things—feed, energy, and labor—that go into producing pork have changed over the years between 1980 and 1999.

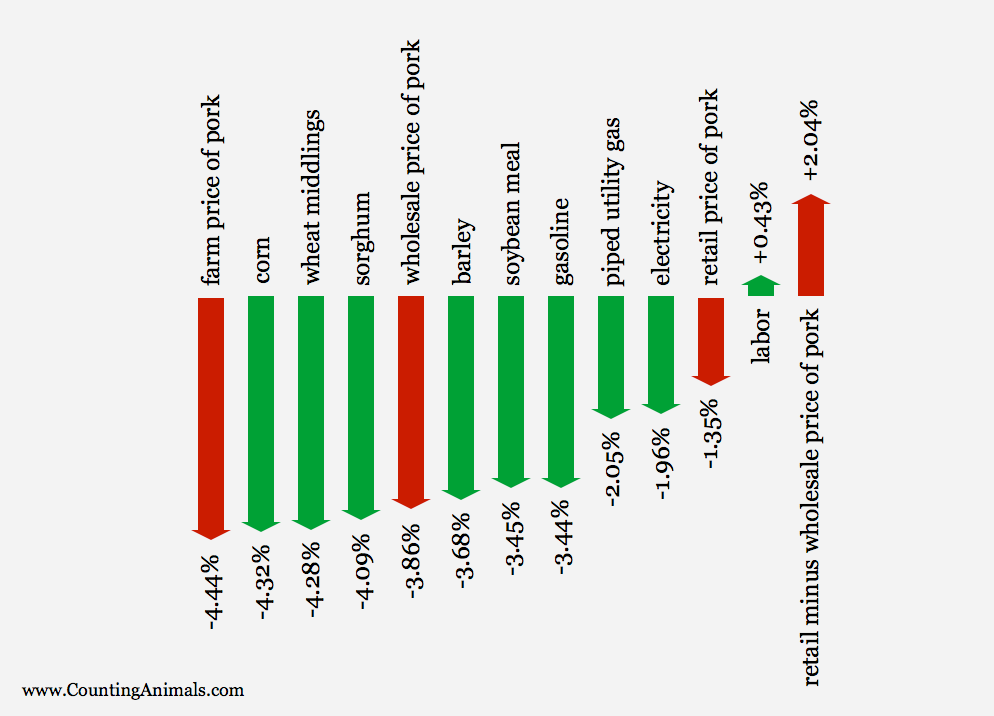

Corn is the majority of grain fed to pigs, but barley, grain sorghum, soybean meal, and wheat middlings are also common alternative feeds. I used the USDA feed grains database to compile prices of these feed grains between 1980 and 1999. Then there is electricity, piped natural gas, and gasoline. I used the data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for these too. Finally, there is labor for which I used the historical data on wages for agricultural workers in the livestock industry collected by the Economic Research Service of the USDA. I inflation-adjusted all the price data, and I used exponential regression as before to compute the best-fit annual percentage change. Since I adjust prices for inflation, some other inputs such as land and machinery, for which reliable month-to-month historical price data are not available, are also implicitly incorporated into this data.

The graphic below depicts the annual percentage change in the prices of inputs that go into producing pork. It also depicts, in red, the annual percentage change in the farm price, the wholesale price, the retail price and, most importantly, the price spread between the retail price and the wholesale price (it is the retail price minus the wholesale price for the equivalent retail weight of pork). This price spread is not the same thing as the gross marketing margin of the retailers but it is a related quantity.

The inflation-adjusted price of almost all the inputs that go into producing pork reduced between 1980 and 1999. Only the reported wages of labor in the livestock industry increased slightly, but labor is actually a small component of the total expenses at a pig operation. Besides, increased mechanization in all aspects of the livestock industry has steadily reduced the quantity of labor that goes into producing pork. For example, according to the Commodity Costs and Returns data compiled by the USDA, the cost of hired labor at a pig farm was about 6% of the total operating costs in 1992 but less than 3% twenty years later in 2012.

So, the farm price—the price farmers got paid—reduced during this period more than almost all the inputs that go into raising the pigs that farmers sell. Clearly, the farmers were nickel-and-dimed to improve efficiency through factory farming to a remarkable degree. But, did the rest of the players in the pork industry actually decrease in efficiency in order for the retail price change to have been so unremarkable? In fact, the difference between the retail price and the wholesale price increased annually by 2.04% during this period. This suggests that the retailers during this time were not as efficient as they could be (did not meet Condition 3) or, more likely, were reluctant to drop prices when costs fell (did not meet Condition 2). Other explanations, such as unusual investments and costs, are unlikely candidates for a sustained two-decades-long trend.

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Average Retail Food and Energy Prices. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- USDA, Economic Research Service. Feed Grains Database. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service. Farm Labor, 1980-1999. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- USDA, Economic Research Service. Commodity Costs and Returns: Hogs. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- S. Kimmel. The Illusion of Anticompetitive Behavior Created by 100 Years of Misleading Farm Statistics, 2011. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- W. Hahn, USDA. Beef and Pork Values and Price Spreads Explained, 2004. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- G. A. Futrell, A. G. Mueller and G. Grimes. Understanding Hog Production and Price Cycles, 1989. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

Now, if the retailers did meet Conditions 2 and 3, would increased factory farming detrimental to animal welfare still have been necessary to achieve the same prices of pork we saw from 1980 to 1999? The majority of the operating costs at a pig farm or a meatpacking plant are unrelated to factory farming, such as feed, taxes, insurance, interest, marketing, general farm overhead and also many capital costs. Many of these costs—such as for feed which is the majority of the costs at a farm—fell between 1980 and 1999. According to the USDA historical costs and returns data, these costs add up to over 80% of the expenses at a pig farm. That leaves about 20% directly impacted by factory farming. There is no survey data on meatpacking plants but since the vast majority of what meatpackers do comes after slaughter—such as cut, trim, grind, package, store, market, and transport the meat—I think it is reasonable to assume that only about 20% of a meatpacker’s costs are impacted by factory farming that is detrimental to animal welfare. Let’s be charitable to the meat industry and double this number; let’s say that as much as 40% of the drop in the wholesale price of pork between 1980 and 1999 was due to increased factory farming detrimental to animal welfare. The wholesale price of pork fell from about 292 cents in 1980 to about 139 cents in 1999, a 153-cent drop, 40% of which is 153 × 0.4 = 61 cents. So, without increased factory farming since 1980, the wholesale price of pork in 1999 would have been about 61 cents higher.

Meanwhile, the retail-wholesale price spread in 1980 was about 126 cents. It is reasonable to expect that the retail portion of the industry could have, at the very least, not increased this inflation-adjusted price spread by neither improving nor decreasing efficiency. If the retail industry met this minimal expectation, the retail-wholesale price spread in 1999 would have been the same at about 126 cents (one should really expect this to be lower but, again, let’s be charitable to the meat industry). Now, in 1999, the wholesale price of pork was about 139 cents. So, if the retail industry met Conditions 2 and 3 since 1980, the retail price of pork in 1999 would have been about 139 + 61 + 126 = 326 cents without increased factory farming detrimental to animal welfare. That would be about 12 cents less than it actually was in 1999!

This is worth repeating: if the retail portion of the meat industry had met Conditions 2 and 3 since 1980 and did not decrease its efficiency between 1980 to 1999, the retail price of pork per pound in 1999 without the use of increased factory farming detrimental to animal welfare would have been about 12 cents lower!

In the period from 1980 to 1999, evidence suggests that increased factory farming was not essential to keeping down the price of pork!

Some have defended the expanding difference between the retail price of pork and the price paid to farmers by saying that the industry has increasingly added more value to its products and that it sells more cooked, cured, trimmed, deboned or processed meat directly to consumers. The argument is that this has shifted free labor in people’s kitchens into paid labor in the meat industry. But, this argument lacks merit because it misunderstands how the retail prices are calculated and the goal behind the methodology used by the Economic Research Service at the USDA. The purpose of the retail price calculations by the USDA is to compare prices for one consistent product over different time periods and not to compare one product representative of one time period with another product representative of another time period. The USDA calculates the retail price values based on one consistent high-volume grocery store product or one consistent composite of grocery store products—and not meat sold in the service deli section or in processed foods. Also, as needed, it revises past retail values to make them consistent across time with regard to the cut of meat. Collecting consistent price data over multiple decades is not trivial, and there are weaknesses in the data. But, it is incorrect to invoke labor shifts as a justification for the expanding price spread.

The price of pork: 1999-2012

Since 1999, both the farm price and the retail price of pork have held more or less steady. But, the meatpacking industry is now even more of an oligopsony with only four meatpackers (Smithfield, Tyson, Swift, and Cargill) controlling over two-thirds of the pork market. Not surprisingly, trends in prices are now more opaque and appear arbitrary. The largest component of the expenses at a pig farm is the cost of corn feed, and it used to be that the largest determinant of the price of farm pork was the cost of corn feed. Now, that is hardly the case. When corn prices steadily increased by a whopping 75% between 2005 and 2009, the farm price of pork, puzzlingly, fell by over 25%! When corn prices fell by over 11% between 2002 and 2004, the farm price of pork inexplicably increased by over 40%! The prices in the industry can no longer be trusted to reflect costs. Prices probably reflect other things like oversupply and undersupply—things that can be engineered by an industry controlled by a small number of players.

Meanwhile, during this period from 1999 to today, factory farming has continued its onward march unabated and small farms have continued to go out of business. The 2012 USDA agricultural census data is not yet released but, from previous census reports, we see that the percentage of pigs sold by farms that sell five thousand or more pigs increased from 66% in 1997 to 88% in 2007, surely with significant reductions in cost. But, during this time—now that the meatpackers increasingly owned many animals or farms previously owned by farmers—none of farm, wholesale or retail price reduced. There is no evidence that these cost savings from increased factory farming are being passed on to consumers of meat. The industry, during this time, is showing no evidence of meeting Condition 1 outlined at the beginning of this post.

In conclusion, there appears to be no evidence that increased factory farming since 1980 has been essential to keeping the price of pork affordable and at the prices consumers have paid for it.

On the price of the meat of chickens

The broiler industry is different from the pork industry in some important ways as regards its economic organization. Most significantly, according to the 2007 USDA Census of Agriculture, over 96% of the chickens sold in the market come from farmers who do not even own the chickens or even the feed (this number is only about 43% in the pork industry). The farmers are under private production contracts by meatpackers to grow and deliver the chickens. There is no such thing as chickens sold by farmers to meatpackers; so, there is no farm price reported by the USDA for chicken meat. There is the wholesale price—the price at which meatpackers sell the meat to retailers—but data on this price is available only since 1990. Further, in a vertically integrated business like the broiler industry, the wholesale price does not capture the costs of factory farming as precisely as the farm price did in the case of pork. So, for the same period we considered for pork prices, 1980-1999, let’s look at the changes in just the retail price.

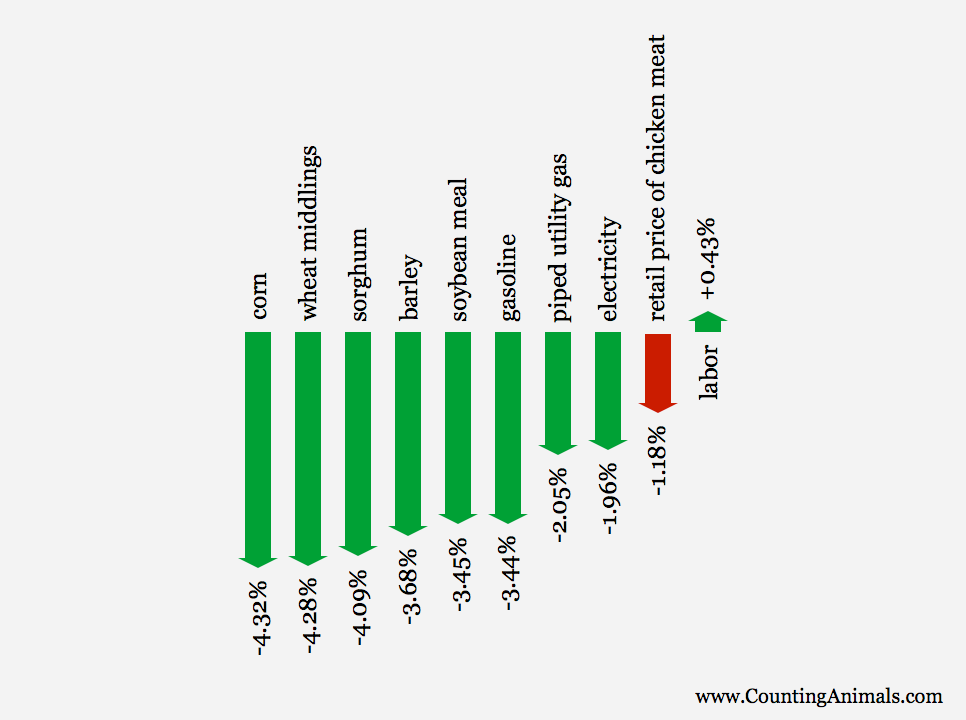

The following graphic depicts the annual percentage change in the retail price of chicken meat, compared against all of the inputs that go into producing chicken meat—actually, the same ingredients as what goes into producing pork but just in a different ratio.

The retail price of chicken, actually, reduced even more slowly than pork did between 1980 and 1999. The argument that the broiler industry did not meet Conditions 2 and 3 is the same as in the case of the pork industry. In fact, because of vertical integration and oppressive production contracts along with consolidation among the meatpackers, the farmers were being squeezed even more intensely than in the pork industry.

Now, for the period from 1999 to today, let’s look at both the retail and the wholesale prices. Using the meat price spread data from the Economic Research Service at the USDA, I plot in the figure below the retail price and the wholesale price per pound of the retail weight equivalent of chicken meat between 1999 to 2013. As before, I adjusted the prices for inflation using the Consumer Price Index tables provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The data for each year is the average of the prices during each month that year, except for 2013 which is for the month of June (the most recent month with available price data). Also plotted is a linear regression trend-line for the retail price as well as the wholesale price.

of chicken meat

The retail price of chicken meat exhibits a different dynamic than the retail price of pork because the market for chicken meat is different: the chicken meat industry is far more vertically integrated than the pork industry; the per capita consumption of pork has been largely stable through the last few decades while the per capita consumption of chicken rose steadily until just recently; chicken meat, being perceived as healthier than pork, has different demand demographics.

- USDA, Economic Research Service. The Economic Organization of U.S. Broiler Production. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service. Poultry Slaughter, 1998-2013. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- The Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production. Economics of Industrial Farm Animal Production. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- Union of Concerned Scientists. CAFOs Uncovered: The Untold Costs of Confined Animal Feeding Operations. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

- The Pew Environment Group. Big Chicken: Pollution and Industrial Poultry Production in America, July 2011. (link, accessed July 23, 2013)

The retail price of chicken meat has been falling slightly in the period between 1999 and today. But, the wholesale price is actually rising. So, the fall in the retail price is probably due to the unique dynamics of the chicken meat industry, but it is not because of cost savings from increased factory farming since the wholesale prices do not show a downward trend.

Meanwhile, the intensity of factory farming has continued unabated. The 2012 USDA census of agricultural operations is not yet released but based on the 1997 and 2007 census data, the percentage of chickens that come from large farms selling half a million or more chickens per year has increased from 48% to 66%. In 1998, the chickens were fattened up to an uncomfortable five times their natural weight; by May 2013, the industry added a whole extra pound of abuse on their little bodies and fattened them faster to an even more uncomfortable six times their natural weight. All of this extra abuse for what purpose? Apparently not to reduce the price of meat, but only to reduce the cost of producing meat! There is no falling trend in the price of chicken meat sold by the meatpackers.

The recent rise in the price of feed is often offered by the industry as an excuse, but this rise only began in 2010. Besides, at least since 1999, the price of feed has held little correlation to the price of chicken meat; so, this reasoning has to be viewed with skepticism. There is always a tendency in any industry controlled by a small number of powerful companies to increase prices when costs increase, but not reduce prices when costs decrease. It is unlikely that the broiler or the pork industry is immune to this phenomenon of what economists call asymmetric price transmission. Also, there is the same apparent arbitrariness in the price of chicken meat as there is in the price of pork—both controlled by a small number of meatpackers and powerful retailers. Meanwhile, of course, the contract farmers, powerless in this vertically integrated market, are being squeezed for every possible cent.

So, for the period between 1999 and today, in the chicken meat industry, as in the pork industry, there is no evidence that cost savings from increased factory farming are being passed on to the consumers.

So, what to make of it all?

Here is the gist of this post if you did not have the patience to read through everything. (Really, you didn’t?)

- Factory farming and the associated degradation of animal welfare reduces costs to the meat industry.

- In the past, through the 80s and 90s, retail prices fell far more slowly than one might expect with any fall in price coming almost entirely from farmers selling their animals at falling prices. It appears that the retail portion of the meat industry was either inefficient or, more likely, reluctant to pass on all of its cost savings from improved efficiency. Evidence suggests that without increased factory farming detrimental to animal welfare but with the retail industry passing on all of its cost savings—and without even assuming any increase in retail industry efficiency since 1980—the price of meat in 1999 would have been no different.

- In the last decade or so (since about 1999), there is no strong evidence that the meat industry has been passing on the cost savings of increased factory farming to the consumers of meat.

- So, in all cases, since 1980, it cannot be argued that increased factory farming—and the associated degradation in animal welfare—has been essential to keeping down the price of pork and chicken meat.

Meat consumers are not saving any more money for themselves simply because the sow locked in the gestation crate barely the size of her body cannot even turn around much of her life or because the chicken they ate could barely support herself on her legs at six times her natural size. It is the meat industry that saved money for these abominations.

Now, a couple of caveats ...

This post is not asking the meat industry to save money for meat consumers by reducing the price of meat. That would just increase meat consumption and harm yet more animals. I am just disputing one of the arguments—unfortunately, widely accepted—the industry uses in defense of the barbarity of factory farming. My purpose is to show how measly little the meat industry has to justify the animal suffering caused by its standard practices.

Finally, even though factory farming of animals to produce meat reduces the cost to the meat industry, let us not forget that it increases the cost to society. And, we must never forget the grim cost that every individual animal trapped in this system is made to pay, with or without factory farming.

py3.9.4 (default, Apr 5 2021, 09:56:39) [GCC 7.5.0]Django(3, 2, 1, 'final', 0)

Comments

Spike

July 23, 2013, 6:08 p.m.

What an incredible amount of work it must have been to compile and analyze this data! Sad as it is, it shouldn't come as a surprise that the same industry that shamelessly tortures animals also twists the truth about low prices.

Sarah Lux

July 24, 2013, 3:03 p.m.

Another brilliant and badly needed piece -- thank you!

Victoria Foote-Blackman

July 24, 2013, 3:54 p.m.

What incredibly interesting and useful research. Yes, the old argument of it keeping the cost of meat lower for the consumer is effectively shot to hell. But since the flesh of animals becomes cheaper to the factory farms, we inevitably see this in the huge margin allowed for deaths due to their 'housing' and 'transportation.' Thank you too for adding the caveat that this is not meant as an incentive to try to get them to further cut costs on the backs of animals, all the while passing on, albeit subtly, increased prices to consumers. If the industry could become cost prohibitive, that would be the ideal.

Brian Brown

July 24, 2013, 7:27 p.m.

Great analysis! You should consider getting this published. I would take out that bit about doubling the predicted change in price attributable to animal abuse from 20% to 40% though, I didn't see a reason to choose an arbitrary number there.

Harish

July 25, 2013, 9:31 a.m.

Spike, Sarah, Victoria, Brian: Thank you for your very kind comments!

Brian: Your point about doubling 20% to 40% is a good one and one I wish I could avoid. But, unfortunately, I don't think there is good data available on the costs at a meatpacking plant. In the absence of good data on it, there is always a chance for error in my first estimate of 20% as being the costs associated with operations where animal abuse involving factory farming is possible. Further, even if my estimate is exactly correct, this does not mean that 20% of the cost savings would come from extra abuse in these operations since percentage of costs is not the same as percentage of cost savings.

I prefer to be conservative and be more charitable to the meat industry in such cases, especially when there is potential for error and the same point can be made while reducing the chances of error. This is why I used 40% for the percentage of cost savings overall. You would be right to say that it is a very conservative number and, may be, even unnecessarily so. But, I think that makes the conclusion of my analysis less likely to be wrong.

bob

May 21, 2015, 11:55 a.m.

i just need u to tell me the price of meat like cow,pigs and stuff plz tell me

Additional comments via Facebook